In our tradition it is commonly held to be the catechism of St. Jerome “L’instruttione della fede cristiana per modo di dialogo” compiled and expanded by the Dominican friar Reginaldo Nerli in 1537.

It is certain that Jerome Emiliani, who needed to teach children, used notes and made use of circulating catechisms.

The spiritual formation of the children was Jerome’s primary goal, even before educating them in the mechanical arts or introducing them to work; he wanted to form an evangelical community and needed to instruct the boys through the teaching of Christian truths in order to orient them to devotion, charity, and work.

The sources all agree that Jerome taught the Christian faith. I cite a few:

- the testimony of the Anonymous: he instituted such a school that Socrates with all his wisdom was never worthy to see: here he taught how by faith in Christ and by the imitation of his holy life, man becomes the dwelling of the Holy Spirit, the son and heir of God;

- letter of Galeazzo Capella to the Duke Francesco Sforza: Jerome committed himself to instruct many children mainly in the divine cult and then in the mechanical arts;

- in the request of May 6, 1531, made to the doge of Venice to obtain the exclusive rights to a patent for wool carding, it is mentioned that “poor derelict orphans are instructed in Christian living for the honor of God and the utility of this sublime city”.

- in the letter of Carafa to St. Gaetano Thiene of January 18, 1534, it is specified that Jerome Miani is captain of a small army “instructed in the way of our Lord Jesus Christ for the good of souls and the increase of the Catholic faith.”

In order to teach his boys, Jerome naturally needed texts and didactic material, which he collected and disseminated. We can say that he copied without any fear what could be useful to him.

- Secondo Brunelli in one of his studies proved to us without a shadow of a doubt, with certainty, that St. Jerome made use of a catechism that had been published in Venice anonymously. It is a catechism of Luther. They are the first Italian translations of his works and precisely in 1525 from the Venetian printing house of Nicolò di Aristotile, said Zoppino, came out anonymously a small anthology of Lutheran writings: Uno libretto volgare, con la dichiaratione de li dieci comandamenti, del Credo, del Pater noster, con una breve annotatione del vivere cristiano. Six editions were printed over a period of thirty years: three anonymous and three under the false name of Erasmus. When Luther saw it, according to the testimony of his student and commensal Johann Mathesius, he exclaimed with enthusiasm: “Blessed are the hands that wrote it, the eyes that saw it, the hearts that will believe what is written in this book, and then they will praise God. This booklet is animated by a fervent Christocentric piety and leaves aside the harsh and cutting polemic with Rome. That the booklet is Luther’s is also the very convincing thesis of one scholar, Silvana Seidel Menchi. The anonymous booklet was used by the Augustinians, the Minim Friars, preachers, and those who needed to instruct the people in the faith.

Jerome’s teaching also fits into this climate of desire for reform of the Church, whose boundaries and methods are not yet well defined. St. Jerome’s catechism begins with a phrase that we find almost identical in Luther’s booklet:

“He is known by Jesus only who knows the things necessary for faith.

We are between 1525 and 1535: this terrible event of separation is taking place in the Church. In 1517 Luther had attacked the work of the Church and the abuse of indulgences, in 1521 he had been excommunicated, in 1530 the Lutherans proposed the confessio augustana in their attempts at dialogue, and at the Diet of Regensburg in 1541 they hoped for a reconciliation. But Card. Gasparo Contarini understood then that reconciliation was impossible on the Sacraments, in particular on the Eucharist (transubstantiation), even if some point of contact could be found on the problem of justification.

It is a period in which the best of spirits – and let us also include Luther who dreamed all his life of being a reformer of the Church – desired renewal and were convinced that reform could be achieved primarily through catechetical instruction. Analyzing Luther’s other catechisms, the Small Catechism and the Large Catechism, both published in 1529, one can see that the Small Catechism has several points of contact with St. Jerome’s Catechism, while the Large Catechism is full of venom towards the Church of Rome. In the great catechism for Luther the Gospel has been falsified first of all by the pope (the chief of all thieves), who uses spiritual power for political and material interests, falsified by the monks, who twist the commandments, and insist on works and the worship of saints instead of the worship of God, falsified by scholasticism. It must be cleaned up by sola fides, not by works, by sola scriptura freely interpreted without the weight of tradition, by sola gratia without the cooperation and free will of man. Indeed, before grace, man is not free: his will is a servant (De servo arbitrio). All these theories on sola fides, sola scriptura, sola gratia will be condemned in one of the first sessions of the Council of Trent, namely in the VI session of 1546.

With clarity, the Church defines that justification comes from God, but always with human cooperation, enlightened by grace. Faced with these clear, certain, and sure formulations, the Holy Office began its investigations, or according to others its persecutions.

Jerome tried to carry out the reform of the Church beginning with the children with whom he lived and whom he took with him, whom he instructed in the Christian faith, committing himself to form with them and with his collaborators a community inspired by the Gospel…

Jerome Miani formulated his own catechetical notes and texts, he used the didactic material in circulation, in particular the anonymous vernacular booklet, “la dichiaratione de li dieci comandamenti…”, today attributed to Luther.

In my opinion, however, many passages of the catechism “L’instruttione della fede cristiana per modo di dialogo” date back to the saint himself. There is his style, there are his expressions that we find in the letters and in our prayer. Friar Reginaldo Nerli, a Dominican, took advantage of the notes and the catechetical texts used by Jerome – after all, a catechism published under the name of a layman would have been risky for those times – to which was united in the printing of “L’esposizione del Simbolo d’Attanasio” by Reginaldo himself (1537), very different in style and formulation from the Instrutione della fede cristiana, where we perceive many stylistic features proper to the language of Jerome.

- First lesson on the cross

St. Jerome’s catechism begins with a meditation on the cross of the Lord: two others follow, truly one more beautiful than the other.

The initial phrase “by the Lord Jesus Christ he will not be known who does not want to know the things necessary for health” is taken from the introduction of Luther’s vernacular booklet. The order, however, is different: Luther speaks first of the commandments, because they make you experience sin, then of the Creed to make it clear that only faith justifies, and finally of prayer, because with it you will feel justified, and at the same time a sinner. Jerome begins with the cross and the three theological virtues, with the works of the good Christian, such as prayer and the sacraments, then analyzes the commandments and precepts of the Church, to conclude with the most beautiful Christian prayers, the Our Father, the Hail Mary, the invocation of the name of Jesus, the gifts of the Holy Spirit, the novissimi, Heaven and resurrection.

Jerome is certain that the Lord’s grace truly justifies us, it is not just a fiducial faith, but a reality that truly and deeply transforms us.

In the first lesson on the cross (pp. 4-5), there is an immediate connection between Christian faith and the sign of the cross, the sign of the blessed Jesus, our victorious emperor. Before the cross the angels bow and the demons tremble. It is necessary to adore the cross with all one’s heart, because it is the synthesis of Jesus’ passion.

One militates under this banner armed with living faith, certain hope, and ardent charity, which always extends to good works. For Jerome, our hope is certain and sure, linked to the possibility of achieving our holiness on this earth. Faith is learned in the Creed.

Hope – it is said with the typical language of Jerome Emiliani – is patiently in the tribulations of this world waiting for the prize of eternal life and trusting that in any case God by his mercy will lead us to that glory of paradise, provided that we do not lack it.

The language here and in other passages is typical of Jerome Miani: I limit myself to a few expressions that seem to me to come from the pen of St. Jerome: in this case how can we not recall letter 2? “This is what the good servant of God does who hopes in Him: he stands firm in tribulations and then comforts him and gives him a hundredfold in this world of what he leaves behind for His sake and in the other eternal life.”

So, the expression provided that we do not lack it, recalls the second letter … if you do not lack it.

What is charity then? It is to love God above all things, so that we would sooner suffer a thousand deaths, than offend the majesty of so sweet our Lord and Father, who wanted to die for us.

Here too “we want to suffer more quickly…” recalls an expression from the second letter “and want to suffer” and our sweet father refers us directly to our prayer which begins with these words.

The catechism then expounds very quickly the capital vices and the ten commandments; then it asks: what must we do so that the commandments may be very easy for us? Answer: we must assiduously pray to God and be fervent in our prayers, having recourse again to his most sweet mother… We are still in the language of Jerome which we find in our prayer: we will have recourse to the Mother of Graces… and in letter 3: much pray that we will be able to see… and in letter 6.to be frequent in prayer before the Crucified.

We have three beautiful prayers that sustain us in our struggle against the devil, the world and the flesh (a liturgical expression that we often find also in Luther’s catechism): the Our Father, the Hail Mary, defined as the greeting of the angel, Elizabeth and the holy church, and the litany of the saints.

- The second lesson on the cross

The first Instruction on the Christian faith concludes with a reflection on the cross of the Lord (pp. 9-11): it is, so to speak, our forma mentis.

The first thing the child must do when he gets out of bed is the sign of the cross accompanied by these words “Fac mecum signum in bonum ut videant qui oderunt me et confundantur, quoniam tu Domine adiuvisti me et consolatus es me”. An expanded paraphrase is made of this in the following instruction (p. 13): “O most holy and most benign Father of ours, save the son of your handmaiden, that is of the holy Church, and make on me the sign of the salutary cross, that you gave me in holy baptism, in which I must be saved, so that the demons with the other enemies of mine, who had me in hatred, may see this sign in me and be confused, and flee, and not harm me, and know that you, O Lord, have helped me, freeing me from them and have consoled me by giving me your grace: Amen. ”

Then, the child must think that when he was baptized, he renounced the pumps of the devil and approached the Lord Jesus Christ’s wages (it recalls in some way our ancient constitutions: strenua acies quae Christi Domino militaret) and therefore has the banner of the cross before his eyes, so that he knows that he must never leave the Lord Jesus Christ and again as one, “mancador di fede – lacking in faith,” approaches the devil. He must consider that Christ died for Him and, therefore, must think that he does not want to be ungrateful to such incomparable love.

Mancador di fede… accostarsi al demonio…(pag.10) recalls again the second letter: o che mancherete de fede et tornerete alle cose del mondo (or you will lack in faith and will return to the things of the world).

Then, another thought about the cross must guide the child: through the cross, his soul is made beautiful, he must not sully it with sins that in the end lead to the perpetual prison of hell, where one never tastes anything but despair, blindness, hatred, weeping, stench, gnashing of teeth, bitterness, eternal fire, perpetual curse (pag.10). The accumulation of terms seems almost to recall with great realism the cruelty of the prison experienced by Jerome.

Thinking about the cross, meditating on the cross, finally considering that through the cross we will reach the homeland of paradise, where we will see the majesty of God, the humanity of Christ, the union of the divine Word with flesh, the angelic nature, the company of the saints, our glorified body, our soul made blessed (pg. 10).

Jerome has some beautiful words about hope. It almost seems to hear what his friend says: he wept for the desire of the heavenly homeland, he filled me with holy hopes.

What is for the boy the conclusion of all these reflections on the cross?

“It will follow that with this lively hope, inflamed with divine love and childlike fear, he will flee fornication, adultery… with the other sins and he will go from strength to strength in the way of Christian life, that is, through charity, peace, perseverance, kindness, meekness with the rest of the precious fruits of the Holy Spirit” (pg.10-11).

Also here some typical stylistic features of the spirituality of Jerome return: flee fornication recalls the letter 6 to flee money and the women’s face and the way of Christian life through charity and peace refers us to our prayer in the way of peace, charity… and the binomial ‘benignity – meekness’ is taken up in adjective form again in the 6 letter: Benign and meek to all, just as the hope kindled by divine love…with the most precious fruits of the Holy Spirit contains an echo of not letting the fire of the Spirit cool, so that it does not ruin everything…

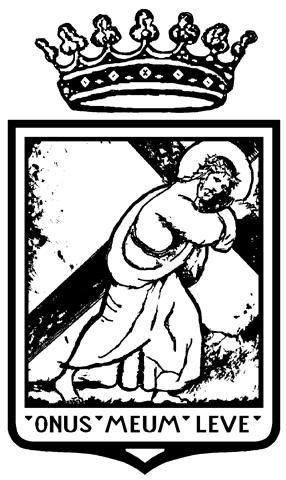

And here is the conclusion of this Christian educational commitment: thus, in his tender years, taking upon his shoulders the yoke of our Lord Jesus Christ, he will easily grow in age, grow in perfection, and ultimately attain the glory of Paradise.

Continuous growth in the life of the Spirit is a characteristic of the Saint’s spirituality, emphasized in particular in the biography of the Anonymous.

- The third lesson on the Cross

But immediately at the beginning of the second instruction, Jerome takes up the theme that is particularly close to his heart: here the Cross is not only forma mentis, but it is forma vitae, the mold into which you must cast and melt your life, to reproduce Christ Crucified. There is much of St. Paul’s theologia crucis here.

“Many and beautiful things you have declared to me in this first instruction, but I through brevity of them have misunderstood them: I beg you to declare to me again the things that matter most” (pg.12).

There is a desire for further study: “First I wish to understand some statements about the holy cross”.

“The cross is made on the forehead, so that we may not be ashamed to confess to you the cross and the name of the Lord Jesus; and on the breast, so that we may remember to always carry in our hearts the memory of the bitter passion, which our Lord Jesus Christ sustained for us on the cross, and therefore, we are inflamed and kindled with the desire to follow him, crucifying and mortifying all our vices and passions and bearing patiently and willingly all the adverse things, which the Lord God allows to come upon us”.

We are still in the presence of the style and thought of St. Jerome, typical of his epistolary. How can we fail to recall the 3rd letter: in patientia vestra… we must bear with our neighbor… the Lord allow this thing because God wants to work in you….

The cross in the mind then, the cross that burns in the heart, the cross loved and followed throughout life. I believe that the first pages, in particular the three lessons on the cross, came out of Jerome’s heart and pen.

The Dominican Friar Reginaldo Nerli assembled the material that Jerome had collected and left to him, giving him the task of writing a catechism that had the security of orthodoxy and the recognition of the Church.

Written by Father Giuseppe Oddone, CRS

Translated by Father Julian Gerosa, CRS