Saint Jerome Emiliani and the Somascan Fathers and Brothers in Venice, Italy, throughout the centuries

Venice, the only city in the world for its waterways, for the light of the sky and the sea, for the palaces that rise and seem to bloom on the banks of its canals and continuously change colors according to the hours of the day. It has a millenary history of state and republic free and independent, and has written a rich page of civilization, art, faith.

It is in the heart of every devotee of San Girolamo Emiliani or Miani (Venice 1486 – Somasca 1537), the Venetian patrician who, after a long civil activity in the republic, at the age of forty, put his whole life at the service of Christ, the Church and the poor, founding the Society of the Servants of the Poor, which with the Council of Trent became the Congregation of the Somaschi Regular Clerics.

The first field of charity was his own home: in the famine of 1527 he welcomed the poor, fed them, distributed to them the bread prepared by him during the night. Here, on February 6, 1531, he renounced, by a notary’s deed, Alvise Zorzi, all his residual assets in favor of his grandchildren and, dressed in poor clothes, he moved to St. Basil.

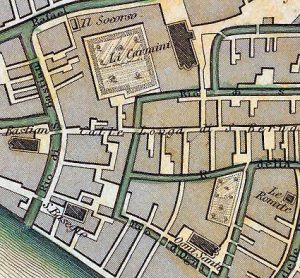

For the derelict putti he created his first specific work (1528) in the area of San Basilio, educating them to work, to a basic study, to prayer and to Christian doctrine.

In the same year, in the Hospital of “Bersaglio”, which he founded and directed together with Gerolamo Cavalli, Jerome Emiliani welcomed the poor of every condition, with particular attention to orphans without any family support. Jerome Miani lived there again when he returned from Lombardy to Venice in 1535. After the death of Saint Jerome (1537) the hospital was also helped by Ludovico Viscardi, a close collaborator of Saint Jerome; the Servants of the Poor remained there uninterruptedly until 1797. Francesco Quarteri, one of the saint’s first companions, assisted of the orphans until 1578.

Thanks to G.B. Contarini, administrator of the pious work, a small seminary of 12 orphans was founded in the Hospital of Bersaglio in 1578. Here Fr. Agostino Valerio received from the Miani family the handwritten life of Jerome Emiliani written by the Anonymous. In 1650 there were six religious who had the commitment to the education of more than fifty orphans and the spiritual care of all the work, that is, the sick, a hundred and twenty orphans, and the church, very popular for the prompt administration of the sacraments and for music.

Girolamo, as the number of his orphans in San Basilio increased, rented (we do not know exactly the starting date) new premises near San Rocco, opening a new school in which he showed all his educational genius of common life with the children, of knowledge and love for each orphan, of work organization, prayer, family spirit.

However, in April 1531, at the invitation of the governors of the Hospital of the Incurables, who were well aware of his ardor of charity, he moved with his orphans of San Basilio and San Rocco to the hospital premises to take over the management.

Girolamo remained in charge of the Incurabili Hospital until the end of April 1532, when he was sent for a charity mission in Lombardy. It is worth remembering that five Renaissance saints passed to the Incurables for a short time: San Gaetano Tiene, Sant’Angela Merici, San Girolamo Miani, Sant’Ignazio di Loyola and San Francesco Saverio.

The Servants of the poor were called to await the education of orphans and the spiritual care of the whole work with a convention similar to that of the Bersaglio. In 1650 it was governed by twenty-five citizens and there were three religious priests and three religious lay people, who worked day and night “with more than ordinary suffering”. She had 63 girls orphans, 33 boys orphans, two separate infirmaries very crowded. Among them was a remarkable Church, cared for without interruption by the Fathers, in which people preached very frequently. The congregation ceased its work here with the advent of Napoleon (1806).

The Hospital of San Lazaro ai Mendicanti (1629-1797), together with the Hospital of the Incurabili, was one of the most important hospitals in Venice. No wonder then that in 1629 the somascan religious were called there, always with the same agreement that focused their work to the education of orphans and the spiritual care of orphans, the sick and pastoral work in the Church, built between 1601 and 1631. In 1650 there were two religious priests and two lay people. The religious ceased their activity during the Napoleonic period in 1806.

After the Council of Trent, the Somaschi, experts in education and training, were called to the direction of the Patriarchal Seminary (1579-1810), which, except for a few brief transfers for contingent reasons (including to the Trinity, until 1630, the year of the plague), had its usual seat in the abbey of San Cipriano in Murano. The best religious were involved, several of whom became generals of the Congregation (father Fornasari, father Terzani, father Vecelli) or bishops (Fr. Cosmi, Bishop of Spalato, and many others). In 1650 there were 19 religious employees (12 religious and 7 lay people) with 40 clerics and 50 noble boarders of the Republic who attended mostly from outside the school. Among them in the last years of the eighteenth century Gasparo Gozzi and Ugo Foscolo completed their classical studies there. The Somascan religious left the seminary with the second Napoleonic suppression in 1810.

The church and seminary were already totally destroyed in 1817.

Another seminary directed by the Somascan Fathers was the Ducal Seminary located at San Nicolò di Castello, directed by the Somascans from 1591 to 1810. Only clerics serving in the ducal basilica of San Marco were trained here at the priesthood: a coveted career, since sooner or later they became canons of San Marco. It was directed for some years by Fr. Maurizio De Domis, then general of the Congregation. In 1650, 10 religious lived there (6 priests and 4 lay people) with 24 clerics and 24 young secular boarders. The schools of the seminaries run by the Somascans were also open to the young people of the Venetian nobility.

The ducal seminary and the church with the adjoining buildings were completely demolished in 1810 to make room for the present public gardens.

Since 1590, in some houses offered by the Patriarchs of Venice and others purchased, the Somascans had settled in the Trinity to create a training community for novices and professed clerics.

Between 1630 and 1670 the Church and Monastery of the Trinity were demolished and the votive temple of the Madonna della Salute was erected; immediately afterwards, on a project by Baldassare Longhena, the religious house was built, which was also the residence of the provincial government of the Congregation, studied for the training of young religious and the seat of public schools, celebrated during the second half of the seventeenth century and in the early eighteenth century, even if in the last phase they suffered from the political decline of the Venetian Republic. The house, suppressed and taken away from the Somascans in 1810, was definitively destined to be a patriarchal seminary in 1818, also because of the interest of our ex-religious teachers in the patriarchal seminary of Murano. It had a very rich library that was stripped of its original contents and was largely lost in the suppression of 1810.

In 1650, during the construction of the church of the Salute, 20 religious lived in community in 30 rooms “old and in bad order”: 8 priests, two professed clerics, five lay brothers, 5 novices. They expected that the large factory of the “Chiesa della Salute” could soon be completed and that a more dignified dwelling would be built for them.

The Accademia dei nobili alla Giudecca was entrusted to the Somascans in 1724: its purpose was to educate nobles who had fallen into poverty at the expense of the state. It usually housed 40 boarders, although the number was only indicative and in 1781 there were 67 boarders. Seven religious, four priests and three lay prefects lived there. It was led by the learned Father Stanislao Santinelli, scholar and educator, author of a documented Life of St. Jerome, still much appreciated today, the lover of Dante P. Gaspare Leonarducci and taught there for a time Father Jacopo Stellini, later professor at the University of Padua.

With the arrival of Napoleon one of the first acts of revolutionary neo-government was the immediate suppression of the College in 1797. The building was confiscated by the state and sold to private individuals.

In the nineteenth century the Somascans made three attempts to return to Venice and continue their activities there. Unfortunately, all three failed both because of the suppression of the Order in 1867 and the consequent dispersion of the religious, and because of the legal and economic difficulties of carrying out the various activities as simple private individuals. We are left with the regret of not having been able to anchor our charitable fervor there in a stable manner, despite having behind us an extraordinary commitment in the field of assistance to orphans, school and culture, which manifested itself in particular in the eighteenth century, the best century for our presence and action in the Serenissima.

In 1850 the orphanage of the Gesuati (1850 – 1881) was entrusted to the Somascan Congregation, with the annexed Church dedicated to the Visitation, where the fathers commissioned and immediately had placed a beautiful canvas of Saint Jerome, but the Congregation withdrew in 1881. The orphanage directed by the Venetian Father Giuseppe Palmieri, the soul of all our works of the Venetian nineteenth century, kept two rings of the chains of San Girolamo, which after alternate events ended one in the basilica of the Crucifix of Como and the other in Central America. In 1881 the fathers moved temporarily to a nearby house of the Cavanis brothers (now a school) and bought the Pisani palace, to open a boarding school with annexed school.

The second work was that of Collegio Manin (1857 – 1867), a charity founded by the Venetian nobleman Ludovico Manin. It started its activity in 1833. In 1857 it was transferred to the area of Lista di Spagna and entrusted to the management of the Somascans who remained there until the suppression of 1867. It had about 300 children, who were given a professional education as tailors, carpenters, blacksmiths, turners. The most gifted intellectually were also allowed access to higher education.

In 1881, the Somascans opened the Emiliani College (1881-1999) in the Pisani Palace, first for the reception of orphans, then as a boarding school and school for the education of young people. Economic and personnel difficulties did not allow the work to continue, which was closed in 1899. The name of Collegio Emiliani passed to the house in Genoa Nervi, which began its school activities on September 1, 1899.

The only work that remains at the Somascans in Venice is the Parish of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Venice-Mestre. An important pastoral decision of Card. Angelo Roncalli was to bring the Somascans back to his diocese, an objective achieved with the assignment to the Somascans of the Parish of the Pilgrim Mother of Mestre, Altobello, an area then poor and peripheral: “I mark this day among the most joyful of my pastoral life in Venice … for the return to their homeland of origin of the Somascan Fathers after a century and a half of desolate absence …. As soon as I arrived in Venice as Patriarch, I immediately felt the desire and the intention to bring this beloved and holy religious family back to its starting point. Today everything is done! (Libro Atti comunità di Mestre, 18 September 1955). The parish, esteemed and well inserted in the Venetian diocese, continues to this day its pastoral activity, its scholastic activity with the parish nursery school, and its charitable work with the daily table of the poor.

by Father Giuseppe Oddone, CRS