Letters of St. Jerome Emiliani – The Third Letter

By Father Giuseppe Oddone, CRS

- Letter-Writing in the Sixteenth Century

Let us focus our attention on the letters of St. Jerome in order to shed some light on his spirituality and his love for Christ.

Writing letters is a very common fact for people of the sixteenth century, because it was the normal means of communication. The great writers also used it as a means of spreading their ideas or even as a means of reporting particular events: see, for information, the book “Lettere del Cinquecento,” edited by G.G. Ferrero, Turin, 1959: in it there is also a letter from Paolo Giovio to Marco Contarini, in which we identify the probable author of the “Life of Girolamo Miani, a Venetian Gentleman,” in which he gives the information of the death of Francesco Ferrucci, killed by Maramaldo, when the Medici returned to Florence in 1530. Some letters were also transcribed in official documents or chronicles and Sanudo is careful to report those, which came to his knowledge, of people or significant events in history; for example, he transcribes in his diaries a 1518 letter from Carlo Miani from Valcamonica, and a 1525 letter from Marco Miani from Cervia.

Of course, we are particularly interested in the letters of our Saint. Before addressing the issue, I would like to make a quick comparison with other letters that have been written by other Saints contemporary to St. Jerome.

- Letters from St. Gaetano Thiene

Of St. Gaetano Thiene we have 40 letters left, some very short, simply notes. He is, like Jerome, a very lucid man in the analysis of events and has a certain affinity of spirit with him; in some cases, we have the same recipients; for example, Giovan Battista Scaini, who was a leader, with his brother Bartolomeo and brother-in-law, Don Stefano Bertazzoli, in San Nicolò dei Tolentini, in Venice.

I just make a quick reference to three letters of St. Gaetano.

- On March 26, 1529, St. Gaetano wrote to Giovan Battista Scaini, who reported that he had listened to a wandering lay preacher, who announced the end of the world: “I beg you, do not listen to him,” and he added: “Be humbly bound to the holy Church of Christ in itself sine ruga licet in ministris prostituta”, in itself spotless, even if corrupt in its ministers, priests, and bishops. The dream of St. Gaetano and that of the Carafa was precisely that of reforming the Church in its ministers.

- Carafa was called to Rome by Pope Paul III with a brief of July 23, 1536, along with Reginaldo Pole and others, for initiatives to reform the Church. We know that Jerome had then gone to Verona in September to greet Carafa on his way to Rome. On December 22, Carafa, in Rome, was appointed Cardinal by Paul III: St. Gaetano, who was passing through Rome, was very puzzled by this choice. On December 23, 1536, he wrote to Carafa’s sister, Sister Maria: “Iudicia Dei abissus; it pleased the Supreme Pontiff to raise to Cardinal, among others, our Father Bishop. May Christ, our Lord, qui potest de lapidibus generare filios Abraham, sanctify his soul according to the dignity he had received… The poor (Carafa was not well in those days) feels the new weight and moans. His most reverend fatherhood, I have found your letter again and he has imposed me that I answer… His most reverend fatherhood sends you a thousand greetings and prays that you help him more than ever… we will try to comfort him inasmuch as we are obliged by the grace of the Lord… with our prayer and that of your daughters we will share in this burden we have had, so that he does not see only the transient dignity, but the present burden and can find its eternal reward; do not rejoice with him, but rather sympathize with him, making him jubilant in heaven and not on earth, as the servants of Christ must do and not as the servants of the world”. St. Gaetano feared for the risks to which the Carafa family could be exposed in Naples.

- In another letter of May 25, 1537, addressed to Giovan Battista Scaini, who had sent a farmer to Naples and was suffering from the death of a dear friend (St. Girolamo Miani?… so Fr. Pellegrini suspects), St. Gaetano wrote: “It remains that we are all prepared by the mercy of God always to strip ourselves of this much-loved garment of mortal flesh and that we are made worthy, when some of us go ahead, of being able to pray for those who remain, and we who remain, have true joy of those who left, with true hope that they went to the Father of all the elect… (It could really be St. Jerome). In the meantime, we are happy to moan all under the grave burden of this mortality, which, if it is well with universal curse above all, yet more and more tribulations and thorns germinates to those who love it more and those who take it more into account, the more they are pricked. Greet for me Sir Bartholomew, Sir Stephen and all those dear to you in Christ … so I hope you do the same with the friends of Verona and of the other places …” (They are the same characters mentioned in the 4th and 5th letters of St. Jerome).

- Letters from St. Antonio Maria Zaccaria

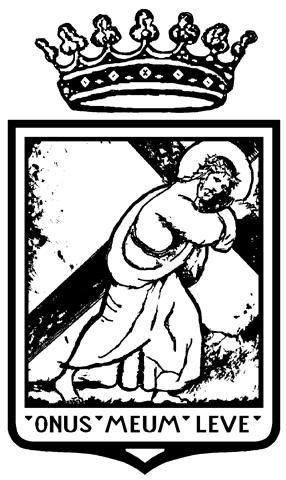

There are nine letters left from St. Antonio Maria Zaccaria. He has another style with a more sentimental and affectionate component, but combined with some stranger and more severe attitudes. His motto is “run like crazy towards the Crucified One”. Here is a brief summary of two of his letters:

- A letter that he addressed to Giovan Battista of Crema, on May 31, 1530. “Rev. Father in Christ, thanked be the mercy of God, who does not reciprocate in all according to my merits; on the contrary, he punishes me only in part, even though I do not feel it because of a certain bad numbness… May your Fatherhood conform to the will of God, to which, no matter what, death or life, (i.e., whatever it takes) I still want to conform myself … Dear Father, do not abandon me and be my saint before God, who will lead me out of my imperfections and pusillanimity and pride…” Then there is a postscriptum: “The ‘Victory over myself’ I will write it with facts and not with the pen”. The seventy-year-old Fr. Battista was completing the work “The victory over myself” that was to be published in Milan in 1531, and had asked the collaboration of the twenty-eight-year-old Antonio Zaccaria to complete it and correct the drafts; but he seems here to decline the invitation with this decisive and voluntarist statement: “I will write it with facts and not with the pen”.

- To our cordial and sweet son in Christ Sir Baptist, “Sweet son in Christ, why are you so pusillanimous and timorous? Do you not know that we cannot abandon you? By experience you must understand the help given to you. We have prayed to the Crucified One: we do not want anything from Him unless He communicates it to you and to your own spirit. (I pray to the Crucified One and I want something that if Jesus grants it to me He must also grant to you). We say no more, but be certain that we will achieve the effects (I will succeed). Christ greets you on our part… May Christ bless you… The signature follows: your father in Christ and mother ANTONIO MARIA, priest and I, A(ngelica) P(aola) A(ntonia Negri). It is a very different style of sharing, almost at the antipodes from that of Jerome, with that touch of priestly anointing, and of femininity inspired by the divine mother Angelica Paola Antonia Negri.

- Letters of St. Jerome Emiliani

The letters of St. Jerome have a rather uniform external epistolary structure and are eminently practical for government: they always begin with an apostrophe to the recipient, they mention letters previously received (except for the Letter to the Company) – in essence, it has been written to me and I reply – they have a schematic and numerical exposition of the content point by point and, usually, they end suddenly without greetings and pleasantries. This is followed by the location, the date, and the signature, and the address written on the back. Two letters were written from Venice by the Trinity in 1535, another from Brescia on June 14, but the year is not specified, another from the Valley of San Martino, the day of the Madona (without the year) and the other two from Somasca, written on December 30, 1536, and on January 11, 1537.

- The disputed date of the Letter written from Brescia (3rd letter)

There is a disputed date, that of the 3rd letter of the Pellegrini’s edition (written from Brescia), addressed to Ludovico Viscardi, who is called here, in the address, servant of the poor, while in the one written from Somasca on January 11,1537, he is simply called brother in Christ.

- Hypothesis of Fr. Santinelli, Bianchini, Landini: 1535

Santinelli, Bianchini and Landini claim that it was written from Venice in 1535 and delivered to Brescia to Barili. This hypothesis is difficult to accept, because the grammar would need to be changed a little. When it is written here in Brescia, it is to be understood as being here or there in Brescia. It is a (grammatical) reason which, besides being very weak, does not seem very plausible.

- Hypothesis Fr. Pellegrini: 1536

Fr. Pellegrini states that it was written in Brescia in 1536. Naturally, to say this, he must assume that Jerome is in Brescia. We know for sure that he was in Brescia on June 4, 1536, for the Chapter. The distance of a letter written ten days before the Chapter, in which the Servants of the Poor of Bergamo had participated, suggests that Viscardi was particularly unhappy with the Servants of the Poor of that community, with shortcomings and misconduct that dated back to well before the Chapter of Brescia.

- Hypothesis Fr. Brunelli: 1534

In one of his studies, Fr. Brunelli maintains that the letter is neither of 1536 nor 1535, but of 1534 (therefore, the first letter in chronological order), and he explains it with these reasons. The Brescia chapter of June 4, 1536 saw the participation of four Servants of the Poor from Bergamo: Romiero, Martino, Bernardino and Zuan tezo, all four who are called into question in the letter. How is it possible that, in ten days, these four Servants of the Poor who participated in the chapter, got into such such disasters to exasperate the Viscardi so as to induce him to write immediately a letter to Jerome in order to have an immediate response? There was no technical time. They would have gone to the Chapter of Brescia (it took a few days); returned to Bergamo (also here the time for moving must be calculated), they would have badly impressed Viscardi, who would have immediately written from Bergamo and had the letter delivered (other days). It’s too much for the space of ten days.

In this letter, Barili asked Miani, who was more expert in practical matters, to respond because in the letter to Viscardi there were various references to Jerome, who had to reproach those who put to the test the patience of the person in charge of the work (Viscardi), to take a stand on the working solution proposed by Jerome in Bergamo, and very much criticized, to reproach Romiero and Martino who were behaving inadequately, to judge Ambone who had made a mistake and did not want to change, and he thought of running away with Zuan Tezo, etc..

If the letter is from 1534 we can better understand some allusions: Romiero and Martino in 1534 are in Bergamo as disciples and cooperators of Jerome, who hopes that they will be won over by the grace of God and his example, to a better behavior. In fact, on June 4, 1536, they are on the list of the Servants of the Poor in Brescia: their improvement has been possible. Romiero was still recommended to Fr. Alexander in his letter of July 5, 1535.

Ambo’s case: Jerome still has some hope on this young man; he must correct himself, otherwise he must be sent to him, there is the risk that he will take away Zuan tezo… but Zovan te(r)zo from Como, more responsible and mature, is at the Brescia Chapter of 1536. A similar case for Bernardino, who, at the moment,cannot be trusted to read to the children; but he too was present at the Chapter of Brescia. In two years (from 1534 to 1536) these four Servants of the Poor, stimulated by Jerome, would have made a positive journey.

Other allusions of the letter of July 5, 1535, which would highlight the organizational and educational abilities of Jerome, who knew how to change and transform people with his charism, would also acquire more meaning: in 1535 it was only a matter of putting some good order in the circles and no longer talking about the beggars; a priest was found, while in the letter of Brescia “everyone looks for a priest and can’t find him”; Romiero was still recommended to Fr. Alexander, so that he may take care of him. Sir Zuane, to whom Jerome had to speak the words of life with a living voice, was reconfirmed in his task of procuring the work for the institution.

Needless to say, Fr. Brunelli’s opinion seems to us to be the most convincing.

- Communication for St. Jerome

We wonder what Jerome thought about communication, what purpose he entrusted to the word; all have their own theory mostly subliminal on the way of contact with others: there are those who communicate enthusiastically and passionately, some in a rational way, those who want to build others, those who present themselves, etc.

6.1. Praying and speaking words of life with living voice

St. Jerome clearly identifies two types of communication: “To Sir Zuane we cannot speak with dead letters, like my letters, but we must pray for him and speak the words of life with a living voice” (III, point 13). Jerome always unites prayer and word; he does not like to write dead letters, but to pray and communicate words of life. It is a biblical allusion to the letters of John. St. Jerome is aware of writing badly, he has no literary affectation, with the exception of the 5th letter put in a good style by a friend and only signed by Jerome. But incisiveness is at stake. Much more effective and sharp are the words written by Jerome in the 4th letter to G. B. Scaini: “The exito de la convertita (the result of your way of behaving) shows that you do not ask the Lord for the grace to operate: et fides sine operibus mortua est: doubt that you are not before God what you think you are. It’s true”. In the 5th letter (always to G. B. Scaini), put in beautiful Italian form, it is said: “We will not fail to remember you in our prayers. Pray to God that he will hear them and that he will give you the grace to understand his will in these tribulations of yours and to carry it out: that his majesty must want something from you, but perhaps you don’t want to listen to it. Be healthy and pray to God for me and recommend me to Sir Stephen.” Jerome’s writing is more incisive and dry, more prophetic; the one transcribed in beautiful Italian form is more diluted, in my opinion with a patina of courtesy and clericalism.

6.2. To show with deeds and words

One of the first aims of communication is, therefore, to pray and speak, with a living voice, words of life. A second is to show with deeds and words so that the Lord is glorified in you.

“Your poor father greets you and comforts you in the love of Christ and observance of the Christian rule, as in the time I was with you I have shown with deeds and words, so that the Lord has glorified himself in you through me. (Beginning 2 letter) The text is a biblical allusion from the first to the last word: poor, father, comforting in the love of Christ, in the time I was with you, showing, glorifying… everything has an evangelical resonance. We find the same expression to show with deeds, even in a strong polemical context regarding the choice of work: “others murmur and have this need for words and we have shown our desire by deeds”. The word is empty if it is not accompanied by facts, by witness.

6.3. Comforting in the love of Christ

Another purpose of communication is to comfort in the love of Christ, to confirm our brothers and sisters in the faith. The word is always born in an atmosphere of faith, it is never an empty word that sounds and does not create, but a word that sounds and creates a relationship of faith, love, conversion.

- Commentary of the Letter III

7.1. The beginning

The letter is addressed to Ludovico Viscardi: unfortunately for many characters, companions of St. Jerome, we have meager news and we sail in the dark. This is what Fr. Landini said in 1945; in 1960 Fr. Pellegrini claimed that some lights had appeared on some of them; today, thanks to the work of Fr. Bonacina, we can say that for many of the first followers of Miani we have more precise documents and news.

Ludovico Viscardi was not a priest, but a merchant friend of Bergamo, active in charity initiatives; he has a certain similar nature with our saint: he will not become a servant of the poor, perhaps, he was for a certain period, but he will always be close to the works of the servants of the poor both in Bergamo and in Venice.

From the beginning of the letter it can be deduced that Viscardi complains that at the hospital of La Maddalena there were inadequate and rebellious collaborators, with whom it was impossible to work, and he is even tempted to give up everything.

Jerome immediately goes to the spiritual problem of Sir Lodovico, a servant of the poor:

– In paciencia vestra possidebitis animas vestras. Quid enim prodest homini si totum mundum lucretur? Jerome, merging two scriptural texts, proposes patience in order to possess one’s soul (Lk.21.19: premonitory signs of the end… you will be betrayed by your relatives and friends…) and not to lose it by adapting to the mentality of the world (Mt. 16.26: Take up his cross and follow me… what good would it do if he gained the whole world and then lost his soul?). Jerome’s ideal is to be in the field with Christ, to be strong in the way of God, because God will do great things in us if we trust in him alone. In some aspects, in a Christian vision of faith, it is the Renaissance theme of the struggle of virtue against fortune, limit, and suffering.

– It seems that you can understand me. First reflection on the code of communication: the two of us understand each other. Jerome knows well the soul of Viscardi, he knows that the values and ideas he proposes can be shared. Then, another image comes to his mind: We are like the seed sown among stones, that is, of those who in tempore credunt et in tempore tentationis recedunt. (Citation of the parable of the sower with the four types of soil: that of the road, that of the thorns, that of the stones, that good). Jerome identifies himself emotionally with Viscardi in the stony ground: we believe here and now, but in temptation and in trial we abandon the field. Temptation is given by the fact that we are faced with brothers who make mistakes and we want to escape from our responsibilities.

– It is up to us to bear with our neighbor, to excuse him within us, and to pray for him, and externally, to try to say (note the combination of praying and speaking) some meek Christian word. It is taken up here clearly by St. Jerome the relationship with the brother who fails. Our first task is to bear with our neighbor, then to excuse him within us (a wonderful thing about St. Jerome according to the Anonymous: “he had great compassion for the bad guys and never thought bad of anyone”), then to pray and say, to pray and say words such as to enlighten his brother at that moment. (cf. Mk 13:11, do not worry about what you have to say at that hour. It will be the Holy Spirit who will give you a word that they cannot resist). We must also recognize that the mistakes of others are also useful, because they teach us to be patient, to know human frailty, to be instruments of God… so that our light may shine and our brother may be enlightened and the Father glorified (Mt 5:11 and Jn 14:13).

– And be careful not to do the opposite when one of these occasions happens… Ocaziun (occasion): a thematic word dear to Jerome because God does not give anything “in vain” and when He sends an occasion, one must not lose it. Any fact in your life is an occasion of grace: even correcting your brothers is an occasion of grace and merit… Jerome demolishes all self-justifications (he lists several of them, among which: I am not a saint; they are not things to bear; and refusing his own gain (grace makes you deserve) say: it would be good if such a person spoke to him or wrote to him and warned him because he is better than me; he won’t believe me; I am not good for these things. Perhaps, Viscardi, in order to avoid correction, urged Jerome to intervene directly or to write to some of the collaborators, but he concludes that we must convince ourselves that only God is good and Christ works in those instruments that want to be guided by the Spirit. We are at the focal point of the spirituality of Saint Jerome, at the working of Christ in those who are pervaded by his Spirit.

– Badly written according to my usual, a second intervention on the code of communication. Jerome knows he is writing badly and prefers direct communication by voice: his message should, therefore, not be sought in the literary form, but in the richness of his spirit. The letter was addressed to Fr. Agostino Barili, who, seeing that Jerome was called into question, entrusted him with the answer. Miani praised Viscardi’s zeal for the work, responds point by point entrusting a further revision of the letter to Fr. Augustine.

7.2. The debt of the apothecary’s store

– De la speziaria agra proveziun (another thematic word in the letters) has been made. Jerome’s work relies on the Hospital: there is a need for very expensive medicines and to obtain them a debt was made that could not be paid; that debt – says Jerome – must have been paid immediately from the beginning, the rest was supposed to be paid month by month. Now it is not possible to meet either of these expenses. We notice how Jerome intervenes in the face of something so apparently trivial, like not having the money to pay a debt.

– We need to take what the Lord sends and use everything, always praying to the Lord to teach us to direct everything toward the subject (objective) and to believe for sure that everything (three times the expression ‘everything’ returns) is for the best and so much praying that we see and, seeing, work on what I need now. A splendid step of spirituality, theology, and style. Here comes out the prophet: a sentence with parallels, anaphoras, and repetitions. Take what the Lord sends us, use everything, always pray to the Lord to help us achieve our goals, believe for sure that everything is for the best, and pray and pray so much that we see and, seeing, work on what is necessary at this time. It is the true spirituality of active life. Every action must be filtered through prayer and the fire of the Spirit. Do what the Lord inspires you to do: you must pray, pray, see, work. God speaks to you in the vortex of events, in active militancy in the field. The reference to the blind man of Jericho is evident (Lk 18:41). Prayer, vision, and action form an inseparable link. Jerome has this icon of the blind man of Jericho fixed in his heart: Lord, let me see! We are so often blind, because we do not know what decisions to make in the action and in the great choices of spiritual life. This image also returns in the 6th letter: to be frequent in prayer before the Crucified One, so that he may open the eyes of our blindness and we may be worthy of doing penance in this world as a pledge of eternal life: to pray and pray to see the practical needs of our lives and to realize our conversion.

7.3. Fr. Zanon warned and begged for the love of God

The Saint has confidence in this priest, he begs him to resist temptation, to bear this slander for the love of Christ and to rejoice in the reward in heaven (Mt. 5,11.12). “He was warned and begged for the love of God (prayer is always part of our communication) that he would resist this temptation, and blessed he be, if he were to be told every evil of him in a lie, which he should bear with great joy, waiting for great repayment in heaven”. It is the spirit of the Beatitudes, a text that must have been very familiar to Jerome, perfectly and deeply assimilated.

7.4. The proposal of work

St. Jerome is a man without education, but he reaches a passionate and sublime style, typical of the prophet, when he speaks of things that are particularly close to his heart. In this case, how to organize the work in the work of Bergamo: “I warn you that not only of these things you should not bother, but if someone spoke about it, that you stop talking; not because the work is something not good, because it is written that qui not laborat non manducat (he should have written not manducet, but Jerome is often approximate in Latin quotations), but since it is proposed a good thing that cannot be done, it is to know for sure that it is Luciferine temptation and is not from God, because God does not do anything in vain.” Jerome is not a dreamer, he is a realist, who proportions the forces in the field to the objective to be achieved: “And this temptation is not a new temptation, but an old one. And in this we are not far from this desire, but we have continually made every effort to put it into practice: as we know publicly that we worked three years in Venice (1529-1531), publicly with the poor derelicts: two years (1532-33) and this is the third (1534) that we worked in rural art in Milan and Bergamo publicly that everyone knows. And Madonna Ludovica (Domenico Tasso’s sister) knows how hard we worked to take home the art of tarpaulins and espaliers (the art of weaving) to the point of working for free. And now here in Brescia we have started sewing caps”.

7.5. The gift of the canvas

It is another proof of how Jerome knows how to read the facts of his life in the light of God.

De la tela I like very much; sed quid inter tantos? (Jn 5:6). Of everything we have to tanks the Lord: Jerome is happy for the gift of the canvas; the concise information is proper to the style of correspondence. But then the words spoken by Andrew to Jesus before the multiplication of the loaves come to his mind. In essence, says the saint, we must maintain a Eucharistic attitude: the gift of the cloth is insufficient for everyone, but Christ who has multiplied the loaves, can meet the needs of his own. Here the immediate passage from the epistolary style to the prophetic style inspired by Scripture is evident. There is also a Pauline allusion: thank the Lord for everything, always keeping a grateful heart.

7.6. Other points of the letter

Following the observations on Romiero and Martino, on Ambone who does not behave well and threatens to take away companions, including Zuan Tezo (he will be present at the chapter of 1536), we talk about the problem of beggars who ask to be hosted and eat at home. Jerome gives permission pro nunc, but says that this question must be dealt with in the chapter: you do not have the impression of being before or after a chapter. This is one of the reasons that may lead to an anticipation of the letter. We must not trust Bernardino for the exercise of reading, he wonders if there are young people capable of learning grammar and finally that beautiful intervention on the code of communication: “Of Messere Zuane, you must not speak to him with dead letters, but you must pray for him and speak to him the words of life with living voice.”

As we have already said, Jerome has this idea of the prophetic word, that is, to communicate in the name of God. In reading his letters we never find the expression ‘I write to you,’ with the exception of one case or two, but always the reference to an oral code: I reply and affirm more than ever – in this world, I say, in time and in the other forever – I cannot tell you more – I want everyone to believe me this word – I make you understand from Christ – I was a bad prophet, although I prophesied the truth – see what the Lord makes me say. They know if the Lord makes me say it – I can say no more than begging them for the wounds of Christ. Jerome aims at a direct communication, always dictated by the Spirit; every now and then his oracular way is fixed in a sentence: if the company is with Christ, we will reach the intent, otherwise everything will be lost – lacking devotion, everything will be lacking – by not working, little the brothers are confirmed in the charity of Christ.

- The inspiring core: the grace of working

Each of us has an idea or a group of ideas within us, which manifest themselves on the outside, which condition our words and our stylistic choices. Methodologically, through thematic words, which often return, we try to go down to the inspiring core that conditions communication and action and then we return to the surface, to the text, trying to interpret and give meaning to what has been said or written. I have identified the inspiring nucleus in the grace of operating. Some of the texts that always appear in particular moments of spiritual reflection enlighten us: God does not work his things except in those who have placed their faith and hope in him alone (here is God the Father) – Christ works in those instruments that are guided by the Holy Spirit (here is Christ who works with the Spirit) – pray so much that we may see and, seeing, do what we now need (here we are the one who work) – the exito of the convert (your behavior) shows that you do not ask the Lord the grace to work et fides sine operibus mortua est (here is the individual person to work)

The grace of working: Jerome sums up in this expression what is divine and human in every action: we cannot separate these two aspects. It is the theme of grace, which will then be specified and defined in the Council of Trent: it is God’s primacy, but always in grace there is our cooperation, there is our synergy. God who works, who created us without us, will not save us without us. And so it is clear what Jerome means by grace to act: it is not an opaque and anonymous act, but it is the word and the action done by the believer, which belong to us, but above all to the Father and the Son, because they are dictated by the Spirit to those who pray, to those who place all their trust and hope in the Lord. It is the Lord who shows you what you must give. How many times does Jerome repeat it: not remaining to provide in this meantime what God inspires you – to keep that best way that God inspires – to follow those admonitions that will show the charity of Christ – to confirm the work with that modesty that Christ inspires him – I pray to God to show him the remedy and the measure. For this reason, Jerome can call all apostolic work a work of Christ (an expression that also appears in the first constitutions of 1555): confirm them and their brothers in the works of Christ. This will to read the facts in the light of God always emerges: understand one another until God shows something else – one could show the Lord nothing else, summon again the friends of the work – if you can give him a charity suddenly, the Lord will show it to you. The grace to work is, therefore, the actions and words illuminated by prayer. Jerome is sure that every event, even the most insignificant, is a word of God for us. If all creation is a solidified word of God, every action we take, every happy or sad circumstance, every material and spiritual difficulty is a word of God for us, it is an invitation to be with Christ in the field, to remain with Him, to persevere usque in finem, that is, until God shows us something that we see being His. Prayer and action are always interdependent because God acts through us; indeed, prayer is participation and support for those who fight in the field: and although I am not in battle with you on the field, I feel the clap and raise my arms in prayer as much as I can. Moreover, the work must confirm the brothers above all in devotion, in spiritual fervor: To Ser Zuanpiero (Giovanpiero Borello, Girolamo’s collaborator in Somasca) to hold that best behavior that God inspires him in order to confirm those of the valley in good devotion – confirm the company in peace – confirm the brothers in the charity of Christ – confirm themselves in the charity of God and neighbor – confirm the brothers in the works of Christ – confirm the work.

But working meets its limit: affliction, poverty, tribulation. Jerome addresses this problem in the second letter by addressing his poor, troubled and tired and abandoned by the physical presence, but not by the heart of their beloved father. He clearly outlines “the good servant of God who hopes in him”. The first, the true, the great protagonist of the work is not man, it is God, it is Christ. We may be tempted to withdraw, but it is in God’s logic to use the poor and the last to do great things.

8.1. Marian spirituality in working

Jerome has a Marian spirituality and two sentences from Mary always come to mind: ‘God has done great things to me,’ and ‘do what Jesus tells you.’ He keeps repeating: God did great things in Moses, in the whole history of Israel, in Mary, in all the saints, in all his friends, in Jerome himself, in the servants of the poor (it has been certified to you by me that God will do great things in you, if you are strong in faith). It is the active spirituality of doing, of the God of wonders, of the God who overthrows the powerful and raises the humble. So he never tires of repeating to do what Jesus shows us, inviting us to imitate Mary who was full of attention to the facts that were happening around her, who would read in the events the will of God and put it into practice. Everything depends on God, but everything also depends on us: everything is up to you, because God will not lack.

8.2. Active spirituality like that of Christ and the apostles

The spirituality of St. Jerome is truly the spirituality of action, of the grace of working, of action enlightened by the Spirit. I quote Fra Battista da Crema, who maintains that the most perfect life is not the contemplative one, nor even the active one, but the mixed one, which is the life of Jesus and the apostles, who merge contemplation and action: “But the third life, which is the more difficult and rare and of greater perfection, because it is necessary that all these two lives, that is, active and contemplative, be in the same person…”. And to reach this state, whether man is working and contemplating, whether in company and solitude, whether distracted and united, look at what difficulty!… Such were Christ and the apostles and some other saints” (Fra Battista da Crema, Mirror of Open Truth, 1532).

- Conclusion

I conclude by reading from the 6th letter the passage where Jerome reminds us that we are a little blind and that we must go to the school of Christ Crucified so that he can show us (the icon of the blind man of Jericho returns): to be frequent in prayer before the Crucified One, praying that he might open the eyes of our blindness and ask him for mercy, because we may become worthy of doing penance in this world, as a pledge of eternal life.

Through the intercession of St. Jerome, let us ask Christ Crucified to show us his presence in the facts and in all the events of our lives so as to understand what we must actually do and so as to continually convert ourselves to his love and mercy.

Translated in English by Fr. Julian Gerosa, CRS