THEY CALLED HIM “FATHER”

The Paternity Charism in Saint Jerome Emiliani and in the Somascan Fathers

By Father Luigi Bassetto, CRS

INTRODUCTION

By Roberto Geroldi, CRS

- Updating courses like the present one are now part of our “continuing formation”, which is so needed for the consecrated life, nowadays.

Updating is an essential aspect of “continuing formation” for it recalls not only the need to be heedful to the present socio-cultural contexts and changes, so that they will not overcome us, but above all our “creative fidelity” to the charism that the Spirit has given us, and, before that, our fidelity to the Gospel, to the Church and to the human beings of today. Such fidelity will help our Congregation to be open to two vital processes: the actualization of our charism and its inculturation (cf Documents of General Chapter 99: “2 -The Somascan charism: a heritage to be lived and to be shared in formation”, p. 16-17).

- “The year 1999, the third and last preparatory year to the great jubilee of 2000, will enlarge the horizons of the believers according to the very perspective of Christ: the perspective of ‘our Father who is in heaven’ (cf. Mt 5:45), from whom he has been sent and to whom he went back (cf. Jn 16:28)” (TMA 49).

We too, being on such path and tension, are invited to enlarge our horizons and we must be so if it is true that, among the members of the people of God, we, religious, are those who should express in a significant way the meaning of following Christ.

We are then projected in the same perspective and also “updated” in the quest of how to be creatively faithful to our charism. It is always so when “the consecrated” are integrated into the ecclesial corps of the Trinitarian communion: the Holy Spirit retells with strength and newness the word that was handed over as a gift to our Founder.

- Since a few years we too, Somascan Fathers, have been looking for a synthesis, for a unifying priority, for the key-word of our charismatic heritage, of our multifarious apostolic experience and also of our Founder.

It is an urgency that is felt by our formators relating to the new candidates; by our confreres who are at work among young people who are looking for a sense in their lives or among those who are marked by problems; by our communities that are managing educational institutes; and also by those who are doing a pastoral activity.

This is also the intrinsic need of being identified and to express ourselves by what we are and by what we should and wish to be.

- Among the attempts that have been done, in the years “after Vatican II”, it seems that the issue of PATERNITY has raised some interest and consensus.

Such issue may be applied to the very experience of Jerome for it explains and unifies his inner journey, his apostolic and charitable activity:

- The “lost” and “rejected” paternity:

– his father’s suicide;

– his troubled and aggressive adolescence;

– his being an adult opposed to others;

– the loss of his relationship with God.

- The paternity “found again”:

– during his imprisonment;

– the “maternal” intervention of Mary.

- The paternity “understood again”:

– the care of his nephews who were orphans;

– the affairs of the republic.

- The “extended” paternity:

– the boys he found in hospital and on the streets.

Since the beginning the members of the Somascan Congregation have been acknowledged and identified precisely as the “Fathers of orphans and works”, giving in this way a clear, “typical” sign of their way of being consecrated in the Church, the “body of Christ”.

Saint Jerome Emiliani has been declared in 1929 by the Pope Pius XI “universal Father of the orphan and abandoned youth”.

Nowadays too the religious who are transferred from a service to another one are encouraged for the change being conscious that wherever and in whatever apostolic field “we can be Somascan”, i.e., fathers.

Updating allows us to perceive the actuality of our being and it encourages us to live it in its fullness.

- Enzo Bianchi wrote in the editorial of No. 39 of “Parola, spirito e vita” [Word, spirit and life] (Paternity, Bologna 1999, p. 3-6): “any word about God carries with it the wounds and ambiguities of language” and “the setting of our saying ‘Father’ to God nowadays is notably different (…) from the years that were characterized by the imperative of killing the father. Nowadays, side by side with the ascertainment of the father‘s absence, comes to light also the father‘s nostalgia. We went from the concept of the ‘paterfamilias’, and also, quite often, of-the father-master, to the concept of the father nullius’, to the father‘s eclipse. From the useless father (…) to a procreation without relationship”.

It is then self-evident that’s the statement ‘God is Father’ has not only theological and spiritual, Christological and ecclesiological, but also cultural, social and psychological aspects” (…) the question that comes at once to light is: “which father?”. The believer must go from the image of a longed for father to the revealed reality of God the Father.

Jesus made such passage, according to Enzo Bianchi, when on the cross he cried out the abandon from the Father: “My God, my God”, and when he handed over his spirit into the hands of Abba.

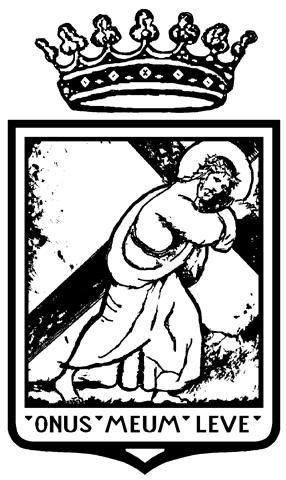

- We too, like Jerome, cannot avoid the ambiguity of being called to be “fathers in a society without a father”, and the passage, compulsory even though “light” (cf. onus meum leve), is the same as Jesus. In fact, Enzo Bianchi concludes: “We are snatched from God’s abandon by our faith in Jesus who cries out ‘my God’

28 to the God who has abandoned him; being grafted to Jesus (. ..) we too can live as God’s children and call on him as Father also in the situations of our life when we feel the cross, the power of the netherworld”. Ambiguities cannot be avoided or baffled: we must acknowledge and face them in the field of the relationship where are evident the remoteness, the separation, the refusal, the negation, the loneliness of those who though being “without a father” do not accept “any father” or a father “in any way”, but wish, perhaps in an unconscious way, to be lead (or, more simply, to be accompanied) in face of themselves in order to acknowledge their “failure” or their being personally and infinitely loved, patiently waited for and embraced by that paternity which regenerates them to sonship.

This is true above all for us; on whatever side we place ourselves, either on the father’s or on the child’s.

- This introduction aims also at explaining the choices that have been made for this updating course:

- In fact, we begin with a contribution given by Mauro Mantovani, a Salesian, a young teacher at the Pontifical Salesian University in Rome, who reflects on the socia-cultural context in which the evangelical proclamation of God’s paternity “jails” nowadays.

- Luigi Bassetto will help us to find out the traits of paternity in Jerome and in our Somascan vocation.

- Manuela Tomisich, lecturer at the Catholic University of Milan, pedagogical consultant in our welcome houses at Somasca, will underline the psycho-pedagogical aspects of the paternity lived by Jerome at his time and by ourselves, Somascans ofnowadays.

- A forum, in which some of us who are working in various fields of our apostolic activities – pastoral, education, charity – will participate, will start a debate and a sharing of experiences that may be useful for the growing up of all of us in our identity.

The co-ordinator will be Ermanno Ripamonti who from his rich experience as a psycho-pedagogue, a judge and more … , will explain his opinion about the relation between “paternity and institutions”.

We are most grateful to those who have conceived the course (Rev. Fr. Capmpana), who have contributed in its actualization (Rev.Fr. De Menech) , and to all those who have accepted to contribute as reporters or attendants.

Thank you!

Fr. Roberto Geroldi, crs.

General councilor, general coordination for formation

Rome, Dec. 28th, 1999

Somascan World Day

To speak nowadays of paternity, and specifically of the paternity charism in St. Jerome and in us, Somascan Fathers, may have a very significant and actual weight.

As many people have underlined, representatives of contemporary culture support the idea that freedom is the negation of the father; it is only before some negative results in young and less young people like: psychological-affective fragility, lack of confidence, anxiety and uncontrolled distress, bewilderment, that those people were compelled to revise such “parricidal culture” and it is now a long time that they began to underline as a highly negative factor in the development of an integrated personal identity the absence of the father … to the point that we can ascertain that when the father is absent there is less freedom, and less ability to manage ourselves, our life and the world.

In such context, then, it does not seem and should not seem a waste of time to speak of the charism of paternity in St. Jerome and in the Somascans.

- “…God the Father, from whom every paternity in heaven and on earth takes its name”

The Anonymous writes: “These days God called to heaven our lord Jerome Emiliani … to the glory of God, to the example for people I wished to write the story of his life and death … I hope in this way that our fellow citizens, adult and young, will be persuaded that the baptism only makes man perfect … and through the example of one of their fellow citizens they may learn how to direct ·their life and from which principles they should take inspiration for their activity”.

And further, having visited the St. Rocco school that had been founded by Miani: “People There did not use to explain the vain sciences of Plato and Aristotle; rather, they used to teach that every man becomes the dwelling of the holy Spirit, a child and heir of God, through the faith in Christ and the imitation of his holy life”.

Such statements are certainly dictated by a spirit which is linked to the typical spirituality of the circles of the “Divine Love”; however, they were, at the same time, the synthesis of St. Jerome’s experience, a unique and deep experience of God as “Father”.

It is precisely the living experience of divine sonship that brings Jerome to formulate some extraordinarily throbbing expressions while he contemplates the crucified Christ, the living manifestation of the paternal love of God: “Sweet Father our Lord Jesus Christ” or “Sweetest Jesus, be not my judge but my Savior”.

He wrote to Scaini: “The Lord will be pleased with you, for, being very kind, he does not look at the results but at the good will”; and also: “Our blessed Lord wishes to put you among the number of his children”.

I think that there is something unique and original in such experience of God’s paternity where the stress on forgiving, care, sweetness and tenderness was not an understood and common heritage among the faithful of his time. Is the event of liberation by Mary at Castelnuovo di Quero to be read as a anifestation of something like God’s maternity? Is the fact of his feeling to be loved by Mary who opens him to the invocation to the Father and to Christ with expressions that are typical of a feminine love?

His God is a Father in whom he can find refuge all the time: “In fact we have no other end but God, the source of all good, precisely as we express ourselves in our prayer; in Him and in no other we place all our trust”“: this is what he wrote to the Company on the 21st of July 1535.

A God who is a provident Father, especially careful of his son in difficulty… as the people of Israel had been a son in difficulty: “He took him out, he performed many miracles, he nurtured him … and gave him as a heritage the Promised Land” (Letter 2, 7).

A God Father whose glory motivates the commitment: “From this will come glory to the Father through his Christ… “ (Letter 3, 2).

A God Father who is felt also as righteous and source of truth, who requires from his children a sense of responsibility for the gifts they have been given and the belonging to Christ, the first-born son: “hey do not know that they offered themselves to Christ… tell them that I’m speaking to them in the name of Christ and that I announce God’s punishment… God will punish them if they do not amend their way of living … As long as I say the truth I dwell in God, for truth comes from God” (Letter 6,4).

From such experience of a God who is a sweet, benign, blessed, righteous, demanding, truthful Father comes the gift and the experience of being the father, following the example of God, of the little ones and the poor: a gift of the Spirit to offer in a special way to the little ones and the poor so that they may taste God’s paternity.

It would be interesting to discover how the characteristics of the divine paternity as it was experienced by St. Jerome will be reproduced by the exercise of his paternity in relation to the orphans and the brothers.

- The charism of paternity in St. Jerome

2.1 He was conscious of being Father

He wrote to the Company: “Beloved in Christ, brothers and sons of the Company … your poor father greets you”; and, speaking of his being away while his brothers and sons are in trouble, he adds: “ …and even abandoned by the physical presence of your father whom you love so much”. He is conscious of the fact that in God and because it is wished by God his paternity becomes unfailing:

“Don’t be sorrowful, for in the other life I’ll be more helpful than what I could be in this present life”. Is it presumption or humble acceptance of a gift given by the Spirit?

2.2 Jerome was acknowledged as a father “They called him father” this is the most exploited title by his biographers for he was a father at all costs. He used to call his boys: “Dear children, little children” and these were not affected words for they were accompanied by concrete actions: he was looking for them, used to give them from his own, to provide for or to build a home for them; he used to wash and nurse their bodies, to give them food and drink. A witness wrote: “Father Jerome used to do any humblest service by himself in caring and directing the little orphans, who let him love and direct them with a more than paternal affection”.

He used to live with the boys and the Anonymous relates as an example of such staying with the boys what happened near Milan when, being invited to stay alone in a suitable place, he answered: “Brother, I thank you very much for your charity and I’m pleased to come there, provided you welcome these brothers of mine, with whom I wish to live and die”.

It was a daily living with them which allowed him to welcome paternally the needs of each one: “How many times I visited him and he used to show me the boys, their commitment, and among them four who were not, I think, more than eight years of age, saying: these ones pray with me and are spiritual; those ones read and write well; those work; this one is very obedient, and the other one is silent”.

A witness to the beatification trial said: “He ordered that the rectors, though priests, should live of what lived the little orphans, and should wear nothing better than what the subjects had; more than that, they should earn their bread by the sweat of their foreheads and the labor of their hands”. This is what he himself used to do to be a model for a promoting identification.

He used to work with them and he wrote: “By our hard work we confirm our brothers in the charity of Christ … Be vigilant so that everybody will work, and do not allow that the will to work, piety and charity decrease, because there stands the foundation of our endeavor”. And he recalled the Pauline saying: “Anyone unwilling to work should not eat”.

The Anonymous writes: “Having gathered in a short time many people, priests and laymen, he entrusted to them groups of poor and abandoned children who, having been healed, clothed, and taught in the Christian way of life, earned their living by their personal labor”.

Such work was not without purpose, and still he exhorted: “Reasonably, make all of them work” (Letter 1, 17).

Manual work and study were done according to the needs and gifts of each one: “I entrust to you the assistance of the boys during study time: be present, ask, test, and intervene very often to make sure that they read aloud … I don’t know whether there is anybody apt to learn the grammar: if you find one let Father Alexander know, informing him about the qualities and the familial situation of the boy” (Letter 3, 28).

Jerome was a father who accompanies his son to the meeting with the world so that he may locate himself in the world by a significant and qualified presence.

2.3 “And call no one your father on earth, for you have one Father -the one in heaven” (Mt 23:9). A child is a gift from God, and only going back to God a child finds the fullness of its life.

We have seen that at St. Rocco School “…people taught that through faith and the imitation of Christ’s holy life man becomes the dwelling of the Holy Spirit, a child and heir of God”. What Jerome wishes to build with his boys is a family of faith.

His whole catechetical work with his boys is enlightening in such perspective. And he who had met with God and his sweet paternity thanks to our Lady “who took him by hand” couldn’t but open his orphans to a filial and trustful piety to Mary. In “our prayer” Mary is located near the Trinity while she asks from Christ every gift for a life lived in its fullness.

A father and a mother who love their son cannot but accompany him to the meeting with God who can reach where human love ascertains its limitations.

- The Somascans and the gift of paternity

The charism of paternity in St. Jerome was continued by the Somascan Congergation that is called to a continuous comparison with its founder and to live nowadays the gift that was given to Jerome.

Both religious and lay can open themselves to the gift of the Spirit by being involved in a paternity that can give full significance to their lives.

I’d like to underline only a few points:

3.1. A Somascan, religious or lay, is called in his journey of faith and formation to a living, deep and inner experience of God as Father. It should be an upsetting experience, lived at the theological, affective and vital level.

All that should bring to the trust in God the Father so that we may find inner appeasement that will let us feel not exposed and precarious before the passage from the need to be cared of, the need to be helped, to the daily and full time care for all those who are in need. In other words, the Somascan should experience the meaning of being a father at all levels without the fear or the anxiety of being alienated, swallowed up by a gratuitous, faithful and daily love that lets nothing to be kept for ourselves.

We need to have the assured certitude that God cannot hide while we are giving ourselves with no reserve and He will open us to the paternal functions that are adequate to our age and personal resources as well as to the needs of his sons.

We cannot but be worried before the feeling of anxiety, distress and the consequent fragility of many religious who do not feel they are called to a paternity according to the style of St. Jerome.

3.2 In the educational experience of the Somascans the presence of Mary cannot be absent: “the woman” who introduced Jerome into the secrets of God’s paternal love in its dimensions of amiability, tenderness, sweetness and benevolence. In this line I believe that the feminine presence inspired by Mary’s attitudes could and should qualify and supplement the Somascans’ gift of paternity.

3.3 The charism of the Somascan paternity is qualified by the “living with them” in reference to the little ones, the poor.

The matter is to build in the boys personal identities that should be characterized by confidence and inner strength, which come to light and develop in those who feel they are accompanied in their daily life, besides some crucial stages, by stable and strong paternal and maternal figures.

I do not believe in Somascans as consultants or experts who supervise the educational endeavor of operators, male and female educators. I see the Somascan religious who work with the lay among the kids, and not through the lay, as some have suggested because of the problem ‘of lack of religious in the endeavors that are mostly devoted to the youngsters’ uneasiness, to the welcoming of minors in trouble and to the formation of youth.

The Somascan paternity finds its expression in an enlightened intention that is directed by God’s plan on each one of the kids.

We are to help the boys to discover the originality of their personality and to be paternally at the service of the boys so that they may discover in themselves God’s dream on them, a dream that can be perceived in the resources that each one has within himself.

All this should bring to a personalized and daily attention to the boys, accompanied by the authoritativeness of those who know they are operating according to some choices inspired by gratuitous love, freed from individualistic and selfish visions.

Every Somascan cannot but compare himself with the modalities and contents of the relationships that Jerome used to actualize with the orphans, and which allowed him to open them to be healthy protagonist in their insertion into the world by their work and profession.

they called him “father “