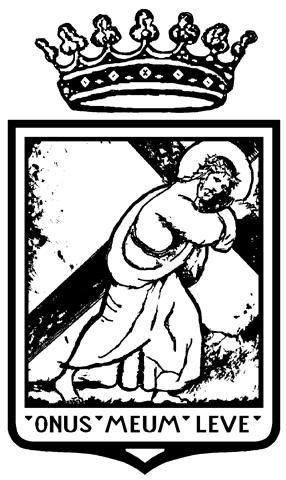

Every time I travel to Venice, following in the footsteps of Saint Jerome Emiliani, founder of my Congregation, I allow myself a moment of contemplation halfway along the path from Campo Santo Stefano to St. Mark’s, in the Church of San Polo. There, immersed in the beauty, art, and spirituality of the place, I pause to admire a splendid Via Crucis (Way of the Cross), the work of a very young Giandomenico Tiepolo, son of the famous Giambattista Tiepolo, completed around 1750.

The Somascan Fathers had a special connection with the Tiepolo family. Giuseppe, Giandomenico’s brother, was a Somascan religious, belonging to the Congregation founded by the Venetian noble layman Jerome Emiliani around 1530. The Tiepolo family, deeply united and religious, experienced a turning point in 1762 when Giambattista and his sons Giandomenico and Lorenzo left for Spain. During their absence, Fr. Giuseppe took care of the villa in Zianigo, where Giandomenico had painted episodes from the life of Saint Jerome Emiliani in the chapel. After the father’s death, Giandomenico returned and resumed his artistic work, as if sensing the imminent decline of the Republic of Venice. The frescoes from that period are now housed in the Ca’ Rezzonico Museum in Venice.

In the chapel of the Zianigo villa, Giandomenico painted episodes from the life of Jerome Emiliani, who had been beatified in 1747 and canonized in 1767. In the painting placed on the altar, the saint’s face bears the features of his father Giambattista. Unfortunately, the sketches and drawings of Giambattista that had been entrusted to his religious son Fr. Giuseppe and kept in the religious house of Madonna della Salute were lost with the fall of the Venetian Republic and the Napoleonic suppression of religious orders at the end of the 18th century.

Giandomenico’s Via Crucis offers me a unique opportunity to immerse myself in the Venetian atmosphere of the 18th century, a time of splendor and decline. By the mid-century, the Republic was experiencing its inexorable decline: its maritime dominion was lost, the Turks threatened from the east, the Habsburgs from the mainland, and European politics had sidelined Venice.

Despite this, in 1750 the city was still vibrant and cosmopolitan, with a stratified society and a flourishing artistic and literary culture. The nobility, devoted to luxury and entertainment, coexisted with a bourgeoisie of merchants and craftsmen who contributed to the city’s wealth and liveliness, animated by festivals and the folklore of the carnival. During these years, art reached extraordinary heights thanks to masters like Giambattista and Giandomenico Tiepolo, Canaletto, and Francesco Guardi, who played with light and color to create emotionally and visually impactful masterpieces.

In the cultural sphere, Carlo Goldoni was revolutionizing theater by giving voice to the aspirations of the bourgeoisie, while Gasparo Gozzi, a former Somascan student, was beginning his career as a writer and journalist. His brother, Carlo Gozzi, opposed Goldoni’s theatrical innovations. Religious life was also flourishing: the beatification of Jerome Emiliani, founder of the Somascan Fathers and considered a Venetian saint belonging to the ruling class of the Republic for nearly a millennium, was proclaimed in 1747 by Pope Benedict XIV, and his canonization came in 1767, proclaimed by Pope Clement XIII, from the Rezzonico family of Venice.

By 1750 the Somaschi had a strong presence in the city, directing the patriarchal seminary, the ducal seminary, the College of Nobles in Giudecca, the Hospital of the Incurables, the orphanage at Santa Maria dei Derelitti, and the school adjacent to their General Curia near the monumental Church of the Salute, which was entrusted to their ministry.

This extraordinary and incredibly beautiful Via Crucis by Giandomenico Tiepolo allows me to relive the cultural and religious atmosphere of that era and to reflect on the ever-relevant meaning of Christ’s Passion. The series begins with Jesus condemned to death by Pontius Pilate, continues through his falls under the weight of the cross, the encounter with his mother and other key figures such as Simon of Cyrene and Veronica, and culminates in the Crucifixion and the burial in the tomb.

The work is celebrated for its artistic refinement and ability to evoke deep emotional involvement. In this Via Crucis, Giandomenico immortalized familiar and Venetian faces, giving the eighth station almost the air of a family portrait. In the scene where the women of Jerusalem meet Jesus, Giambattista is depicted holding a halberd, and Giuseppe is identifiable by his distinctive triangular haircut and prominent ears. The women — his sisters — wear Venetian garments of the time, and one of them, wrapped in an embroidered cloak, offers her son to Christ.

Surrounding Christ, whose noble face reflects suffering, are other positive and negative characters: those who empathize with Jesus’s Passion, the indifferent onlookers — such as the two men in the ninth station who watch Jesus fall a third time, seated on a large polished stone inscribed with the date 1747. Giandomenico was 20 years old when he painted this scene, and that same year Jerome Emiliani was declared Blessed.

The enemies of Jesus often wear Turkish attire — Venice’s traditional foes. There are also those who question the meaning of Christ’s Passion and gaze directly at the viewer, like the Venetian nobleman and the elegantly dressed woman in the scene where Jesus is stripped of his garments.

The figure of Jesus is central, dressed in a red tunic — symbolizing his humanity and Passion — and a blue cloak — signifying his divinity. The enormous cross weighs on his shoulders, surrounded by characters of all ages, from children to the elderly; their reactions vary: empathy, indifference, hostility.

The work also stands out for its scenography and architecture, which alternate between Roman, Renaissance, and Baroque elements. The skies, often traversed by flocks of birds, add a dynamic element to the scenes. Despite the drama of the narrative, everyday Venetian details emerge in the 14 panels: bejeweled ladies in contemporary fashion, nobles, merchants, halberd-bearing soldiers, turbaned Turks, and curious children.

The use of vibrant colors enhances the vitality of the scenes and invites the faithful to identify with the work, making the meaning of Christ’s Passion ever relevant. Giandomenico Tiepolo suggests that this Via Crucis does not belong solely to the past: it is an eternal drama that traverses every age and involves every individual in the Christian story.

The Via Crucis can be viewed online at:

👉 Via Crucis by Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo – Wikimedia Commons

The paintings from the villa in Zianigo, including the chapel of Saint Jerome Emiliani, can be viewed here:

👉 Giandomenico Tiepolo – Zianigo | Ca’ Rezzonico Museum

Fr. Giuseppe Oddone, CRS