Introduction

The meanings of “devotion” in our Sources are essentially two.

- Full dedication to God alone. (1Let 9.15.18.22; 2Let 7-9.19; 6Let 13; OP 7).

- Devotional practices (especially when found in the plural form, like 1Let 8.20), and prayer in general.

The first meaning is clearly wider and more important, for it is essential, ontological, and not just functional. Even in our everyday language we speak of devotion in the sense of a complete dedication to a goal or a person, which takes priority over everything else.

The second meaning of prayer and devotional practices is complementary, being an indispensable expression of the first.

This contribution builds upon that previous one, and especially on the first basic meaning.

Background of Christian Consecration

Christian consecration to God is founded on the common basic consecration we all have in the baptism. In baptism we are buried with Christ in his death, in order to share in his resurrection. We are dead to sin and the life we live now, we live for Him.

The “special consecration” taken by some of us builds upon and develops the common consecration of baptism. While most Christians continue to live an ordinary life in the world, some of them are called to live a life that is not ordinary (and in this context, it makes no sense to try and make it look ordinary: its charm and attractiveness resides precisely in the fact that it is “not normal”).

Forfeiting one’s rightful prerogatives to self-determination, private property and human love (even erotic love) has nothing to do with rejecting sin. With our vows we give up something good, something holy, not something defiled.

This is a sacrifice. Some people dismiss it as “unnatural”. We know that not everyone can understand it (Jesus himself acknowledge it: Mt 19:12), and we know by experience that there is a struggle that comes with it. Those who do not seem to understand it find it absurd, meaningless. I remember even one of our former religious: when asked why he was quitting the congregation, he who was so enthusiastic about working with abandoned children, he replied that he had understood that he could do all that “even without being a religious”. A meaningful reply indeed.

Why, then some people are ready to take on this struggle, to pay this high price?

There may be, of course, reasons of convenience or self-realisation that had been present, at some stage and to some degree, in every one of us. God knows that our attention, at the beginning, must be captured by aspects of our vocation that, though part of it, do not constitute its essential core. In the course of time, however, we realise the feebleness of those peripheral aspects, and aim straight to the core.

And the core is this: God has touched our life with his love.

There was a moment, or a period, some time in our life, when we experienced the loving presence of the Lord in such an unmistakable way, that we could no longer take our eyes away from him. He filled our vision, he enticed us, and we allowed ourselves to be enticed. He overpowered us, sweetly, with his love, and we gladly let him (Jer 20).

The book of Exodus described magisterially one such experience as the “burning bush”.

There is no turning back. Our life has taken a hairpin turn. We realise that only by the gift of our whole life can we reciprocate the love of the Lord. And we did it.

The struggles that may come afterwards can only be withstood, and acquire meaning, in the light of that primordial experience of God, which is perpetuated in our daily exchange of love with Him. Otherwise, it is meaningless. And so it becomes, when we lose sight of our pristine Love.

The “burning bush” of St. Jerome

St. Jerome did not leave any first hand account of his experience of the burning bush. We only have the account of an observer who, we can reasonably presume on the basis of his writing, was in deep confidence with him, and could pick up the story from the source.

The Anonymous depicts the whole spiritual journey of St. Jerome, from his conversion up to his death. There is no need of repeating it here, it was worthily examined by Fr. Pellegrini. A synthesis of it in English language is available with me. The elements contained in that account are very relevant, for they are extremely concrete. They show a path that every one can trod.

We do not know the exact moment of his life when this turning point took place. It has certainly been a process that unfolded slowly, a gradual change of St. Jerome’s life and habits, starting from the experience of the night of September 27th, 1511. The Anonymous, however, makes no mention of St. Jerome’s miraculous escape from prison. He does not even recall a particular event in his later life. He places, however, the more intense period of his conversion after the death of his brothers and his shouldering the responsibility of their families. Later, therefore, than the moment of his liberation.

We may confidently make an inference. In his later life, St. Jerome displayed a great degree of dedication and involvement in the Oratory of the Divine Love. He lived and moved almost exclusively within its boundaries, as his journey to other Italian towns can prove (Fr. Sebastian Raviolo rightly underlines this fact in his history of the congregation). We can therefore presume that the encounter with the Divine love had been fundamental for his conversion.

The Oratory arrived in Venice some time after the sack of Rome (1525). His members were compelled to fly the Eternal City for their safety, but this circumstance proved providential. As the first persecution in Jerusalem caused the Gospel to be preached elsewhere, even to the pagans, so the Divine Love spread to a number of other Italian towns (until then it had been present in Genoa and Rome, and Naples subsequently). The Oratory of Rome was extremely fervent, and its members were prominent in the Church and in the society of the time.

Among those who sought refuge in Venice, we find Bishop John Peter Carafa and St. Cajetan of Thiene, founders of the Clerics Regular (Teatines). St. Jerome, whose spiritual guide until then was a Venetian Canon Regular, now entrusted himself to the care of the fiery Bishop. I believe it obvious to see this encounter as the moment in which St. Jerome’s conversion took a sharp turn, gathered speed and momentum. It would be extremely interesting to examine the statutes of the Divine Love to understand St. Jerome’s spirit in a better way.

The account of St. Jerome’s conversion recounted in An. 5-6 must be understood against this background. St. Jerome’s “burning bush” had been his encounter with the Oratory of the Divine Love.

The signs of this primordial experience are found in St. Jerome’s letters, where he exhorts and confirms his companions with such an ardour that can hardly be found in a person who merely repeats moral recommendations learned by others. That ardour is not perceived, for instance, in the biography of the Anonymous.

St. Jerome’s strokes

There are a few brush strokes by St. Jerome that enable us to define his way of understanding his complete dedication to Christ. They are taken from his Testament, in the biography of the Anonymous, and from his 6th letter.

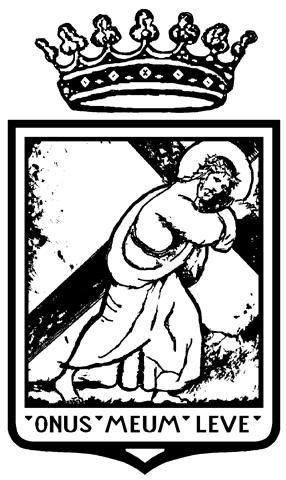

- Follow the way of the Crucified

- Hold the world in contempt

- They have offered themselves to Christ

- They are in his house and eat of his bread

- They allow themselves to be called servants of Christ’s poor

- Follow the way of the Crucified

At that turning point around his encounter with the Oratory of the Divine Love, St. Jerome often listened to the Word of God. The Word of God, penetrating his heart, led him to the contemplation of the Crucified (An 5,1-2). It is in this context that he coined the beautiful prayer “O most sweet Jesus, do not be my judge but my saviour”.

He wept in front of the Crucified. The discovery of the infinite love of God for him (the Son of God gave his life for me, Gal 2:20) had the immediate effect, by contrast, of highlighting the sinfulness and unfaithfulness of his past life.

Remorse paved the way to the reformed life embraced by the brothers of the Divine Love. The initial involvement snowballed, until St. Jerome eventually left everything and served the Lord, full time, among the poor.

The centrality of the experience of the Crucified emerged at crucial moments, even in the scanty documents that are left to us.

- It is his crucified Lord he recognised, loved and served in the poor (An 14,7: “above all, he loved his dear poor who best represented Christ for him.”).

- It is the Lord crucified and risen who alone can ensure that the Company reach the goal (1Let 5-6: “But the truth is that I am nothing. And believe, as certain, that my absence is necessary: the reasons are infinite, but if the Company remains with Christ, the goal will be reached; otherwise everything will be lost. The thing is debatable, but this is the conclusion. Therefore, pray to the pilgrim Christ by saying: Remain with us, Lord, because it is nearly evening.” The biblical quotation carries the weight of the passage of the disciples of Emmaus).

- It is only the love of the Lord, discovered and expressed in the Crucified, that can urge us to do our utmost to help the people entrusted to us (1Let 18-20: “Tell sir priest Lazzarin to have those little sheep for recommended, if he loves Christ.”).

- It is the crucible of the cross that St. Jerome recalls when he wants to confirm his wavering companions (2Let 11-15: “He wants to test you as gold is tested in a furnace: the dross and impurity that are in the gold are consumed in the fire, while the good gold is preserved and increases in value. So it is for the good servant of the Lord who hopes in Him: he remains steadfast during tribulations and then God comforts him, giving him both a hundredfold in this world for the things he leaves behind out of His love, and eternal life in the next. So He did with all the saints. So He did with the people of Israel: after many tribulations in Egypt, not only did He led them out of Egypt with many miracles and fed them with manna in the desert, but He gave them the Promised Land. Even you know it, since it was assured you by me and by others, that God will do the same with you, if you are steadfast in faith. And right now I repeat it and affirm it more than ever: if you remain steadfast in faith during temptations, the Lord will console you in this world, will lead you out of temptations and will give you peace and tranquillity in this world. In this world, I say, temporarily, and in the next for ever.”).

- It is the endurance of the sufferings related to one’s cross that manifest the authenticity of one’s commitment to the Lord (2Let 30, ending: “However, they are not to trust in that [in the help of the reputation of St. Jerome], but in the Lord, and are to be willing to suffer.”).

- It is to the primordial experience of the Crucified that he leads back his erring companions, to help them to focus once again on the ideal that attracted them at the beginning, on their first love. He seems to know no way other than this or more effective than this (6Let 12-13: “Therefore, for now I do not know what else to say but to beg them for Christ’s wounds to be mortified in all their external action and, within, filled with humility, love, fervor; to bear with one another; to be obedient and respectful to the commesso and to the ancient holy Christian rules; to be meek and kind with everybody, especially with those who live in the house; and above all, never to grumble about our Bishop, but always – as I have written in all my letters – to obey him; 13 to be assiduous in praying before the Crucified by asking that He may open the eyes of their blindness and seeking mercy, that is that they be made worthy to do penance in this world as a guaranty of eternal mercy.”). St. Jerome hopes that, by bringing them back at the feet of the Crucified, his brothers’ ways may be amended.

- And finally it is a red Cross that St. Jerome draws on the wall opposite to his death bed. He wishes to die in the same way as he was reborn to Christian life: in contemplation of the love of the crucified Jesus.

The Crucified Lord received the complete devotion of St. Jerome. That was his consecration.

- Hold the world in contempt

The second recommendation of St. Jerome’s testament is a consequence of the first.

It may sound unwelcome to our ears, nowadays. For a few years it had inexplicably disappeared from all quotations of the testament of St. Jerome made by our official documents, by some General office bearers of our Congregation. Only the other three recommendations were quoted. This one was silently skirted away.

The meaning of this expression, however, is not that the world is just something despicable and evil. St. Jerome would have never involved in the matters of this world as he did, had he believe it to be unworthy and defiled.

Give to everything its own objective value, neither more nor less than that; do not allow your heart to grow attached to worldly goods or creatures, for they are bound to end and leave your expectations unfulfilled. Only God can fulfil the deepest longings of your soul. This, I reckon, is a healthier understanding of the second of St. Jerome’s recommendations.

Our life sets us continuously in front of choices to be made, bifurcations of our road ahead. Such choices are not necessarily between good and evil. Most often they are between two different goods. It is God’s will that indicates that one good is better, for us individually, than the other one. It is his plan that leads us. When we marry we choose one girl, without meaning that all others are bad.

The experience of the burning bush leads us to realise the fallibility of everything else, even the holiest realities. Our choice to follow the Crucified needs to be renewed continuously, for the world is positively attractive, and our attention and focus may fade. The awareness of the real value of the world will bring us back to Him who alone never fails. “You have created our heart for you, and our heart does not find rest until it rests in you.” (St. Augustine, check the quotation in the Confessions)

- They have offered themselves to Christ

The last letter of St. Jerome available to us is extremely passionate. It was called for by a situation of distress caused by some Servants of the Poor who were not faithful to the covenant with the Lord. This context makes it relevant to us, who wish to probe St. Jerome’s understanding of consecration.

In this letter St. Jerome manifests that his companions had taken his same commitment to the Crucified Lord. The Servants of the Poor were not merely a group of people devoted to philanthropic works. The total devotion of St. Jerome to the Crucified, had passed on and embraced by them, too. St. Jerome’s experience and consecration had become a way of life for others as well.

I choose to take only two details.

- They are in his house and eat of his bread

Two basic needs of a human person are looked after by the Lord: shelter and food. When we offer ourselves to Him, the Lord looks after us. We live of his providence. We do his work, and he gives us what we need. Mt 10:10: “labourers deserve their food.” The fact that our needs are looked after must be a spur to a more radical faithfulness to our consecration to the Crucified. It cannot lead us to diminish our commitment, to take things easy. Nor can it justify such behaviour.

Providence is a sign of God’s faithfulness to us. We hold everything in common with the poor, and our needs are looked after. God’s faithfulness calls for our faithfulness, too.

- They allow themselves to be called servants of Christ’s poor

We bear the Crucified’s name. We have made a public commitment, we are bound to a public witness. It is not us whom people would blame if we make a mistake. We bring disrepute to the Lord. Our unfaithfulness becomes an obstacle (a “scandal”) for other to believe.

by Father Pierluigi Vajra, CRS